Evaluating text entry on the information level using throughput: Part 1

in posts

This is a blog post of our CHI 19 paper, Text Entry Throughput: Towards Unifying Speed and Accuracy

in a Single Performance Metric. It was conducted by me, Shumin Zhai, and Jacob O. Wobbrock.

Do you know how well you type? In text entry studies, researchers currently use two metrics to evaluate a text entry performance: the speed and the accuracy. Speed is usually measured by Word Per Minute (WPM), and the accuracy is usually measured by the error rates.

Problem Emerges

However, using two metrics to evaluate the performance might cause problems. For example, Ray is typing with the same keyboard. If Ray is in a hurry, he might type faster with making a lot of errors; or if he types carefully, he might type slowly and accurately. The example is shown in the following table.

| Speed | Error rate | |

|---|---|---|

| Type in a hurry | 50 WPM | 0.1 |

| Type carefully | 30 WPM | 0.01 |

Then how do we measure the performance of Ray and the keyboard with the two speed-accuracy conditions? Can we draw a firm conclusion on that? More importantly, can we overcome the effect of speed-accuracy tradeoffs?

In this paper, we present a metric called text entry throughput. It evaluates the overall text entry performance, and is stable across different speed-accuracy conditions. It measures the information being transmitted through the process based on the information theory.

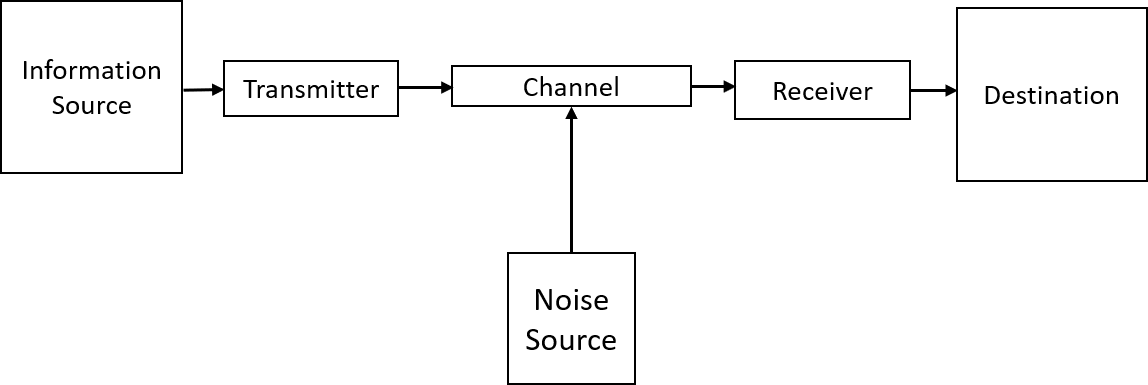

So how does it works? Well, to understand it, let’s first have a look at the communication system in the Shannon’s famous paper of information theory, A Mathematical Theory of Communication. It illustrates that the information generated from the source, received by the destination, and transmitted through the channel. Here the transmitter and the receiver play the role of encoding and decoding.

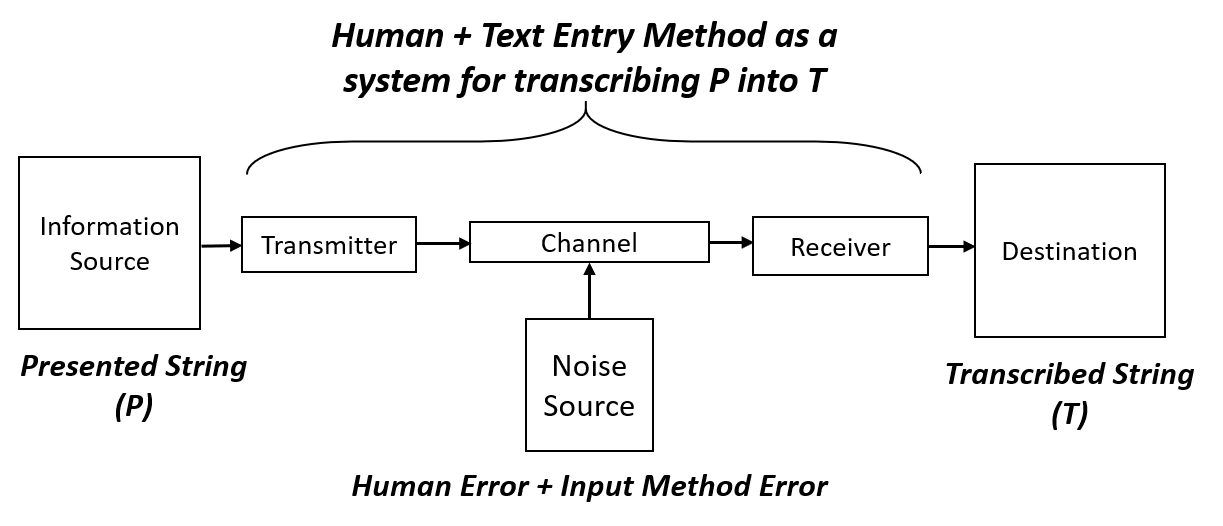

In a text entry study, a string (which is called the presented string, P) is shown to you, and you transcribe it using the input method. The final string you typed is called the transcribed string (T). Thus if we think about it, the text entry process is exactly an example of the information transmission process. We can map each part to the diagram: P is the source, T is the destination, and human + text entry method together is the middle part, transmitting information from P to T. During the typing, errors might happen, thus noises are introduced.

The Discrete Channel with Noise

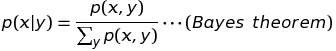

The information being transmitted in a text entry process is discrete, because we are typing character by character. Shannon called the channel in this kind of system “the discrete channel with noise”. And fortunately, he has a concrete example on how to calculate the information transmission rate (the throughput) of the channel. Let’s have a look:

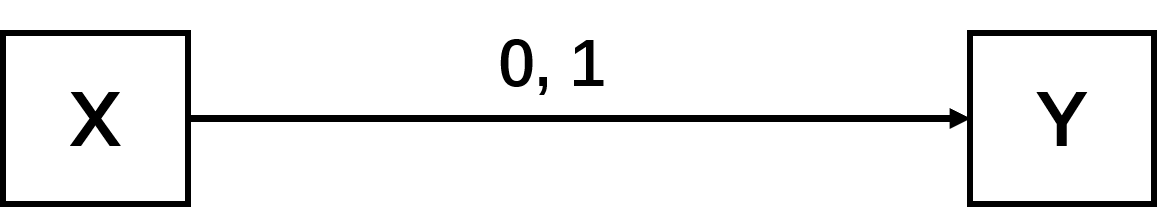

In the image above, there is an information source X, which is sending symbols 0 and 1 with equal probability 0.5, at a rate of 1000 symbols per second to the destination Y. During the transmission, because of the noise in the channel, there is an error rate 0.01 which means 1 out of 100 symbols is sent errorly into the other one. What is the information transmission rate (throughput) of the channel?

The first guess might be 990 bits/sec. Because the source information H(x) = -0.5 log2(0.5)-0.5 log2(0.5) = 1 (the information here is also called the entropy. You can find how to calculate it here). The information being transmitted is thus 1000 bits/sec. With the error rate, it will be 1000 x 0.99 = 990 bits/sec. However, the error rate only tells us about the quantity of errors, not the position. For example, if we received a thousand 1 symbols, even we know that there might be a 0, we do not know where it is. In other words, 990 bits/sec is more than the real information being transmitted, because we lack the location information.

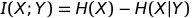

The correct way is to first calculate the mutual information. If we look at the image below, the pink circle represents the information of X, the blue circle represents the information of Y, then the intersection part of the two circles is the mutual information (I(X; Y)) of X and Y. It represents the amount of information that both X and Y have. The part of the information that X has but Y doesn’t is represented as H(X|Y) (or Hy(X) in the paper).

Shannon provides the formula to calculate the mutual information as

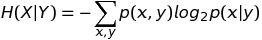

and also, The way to calculate H(X) and H(X|Y) is

Thus if we have P(x), P(x, y) and P(x|y), we can get the throughput of the channel. Also P(x, y) = P(x)P(y|x), and

Thus if we get the P(y|x) and P(x), we can get the throughput. In the text entry process, P(x) represents the probability of character x appearing in the presented string P (in other words, the character distribution of P). P(y|x) represents the transmission probability of typing character x into y.

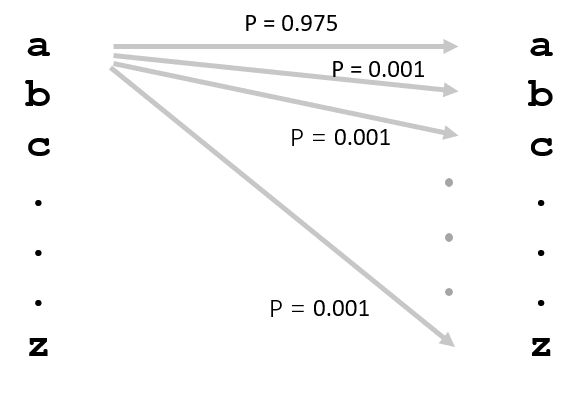

The Null Character

But wait a second. The above calculate is perfectly suitable when there are only substitution errors (typing a character into another one). However, there is also omission errors, where characters are mysteriously omitted (like typing “abc” into “ac”); and insertion errors, where characters are mysteriously inserted (like typing “ac” into “abc”). In both error types, the text length of the source (P) and the destination (T) are different. Thus we cannot calculate P(x, y), because there is either no x, or no y. How do we cope with the problem?

Well, the solution in the paper is to introduce a null character Ø. Ø is only a placeholder character to represent the omission and insertion errors. Thus the omission error becomes Ø is typed into another character, and the insertion error becomes one character is typed into Ø.

In this way, we can get all probabilities of p(x) and p(y|x). Problem solved! And we get the throughput for text entry.

However, the throughput now is still not ready for use. It is facing two practical issues. We will continue discussing in the next post. Or you can refer to the paper for a full explanation.

For your convenience, we open-sourced our text study interface TextTest++ here at GitHub, and also our algorithm for calculating the throughput here. Enjoy!