Evaluating text entry on the information level using throughput: Part 2

in posts

This is a blog post of our CHI 19 paper, Text Entry Throughput: Towards Unifying Speed and Accuracy

in a Single Performance Metric. It was conducted by me, Shumin Zhai, and Jacob O. Wobbrock.

Alright, time to introduce the practical issues of text entry throughput we calculated so far.

Practical Issues

Issue 1: p(x) varies with different phrase set.

Phrase set contains the presented strings (P) in a text study. Thus it represents the information source. We intend to use throughput to measure the performance of the channel. So it should not be dependent on the source information. However, different phrase sets (different sources) have different p(x), leading to different H(x), and can thus change the value of throughput without changing the channel. For example, considering the following two phrase sets:

Set 1: “abcde”, “abcde”

Set 2: “abcde”, “eeeee”

There are more “e”s in set 2, thus p(‘e’) of set 2 is larger than that of set 1. And H(Set1) is different from H(Set2).

However, we do not want the source information to be changed. Because if not, someone can “cheat” by using a fine-tuned phrase set to increase the H(x), which increases the throughput without improving the text entry process.

The practical solution we offer is to use the letter distribution of the target language. In the paper we focused on English, thus we used the English letter distribution to calculate the source information. The distribution can be found here. We used “a-z” plus the space characters, and normalized the sum of their probability to 1. To fix the source information, we did not include the null character in calculating the source information, because the number of the null character depends on the omission and insertion errors, which depends on the text entry process.

Issue 2: p(y|x) is too difficult to get.

In theory, to calculate the throughput, we have to get the probability of typing each possible character into each possible character. This requires a lot of observations in the text experiment. Due to the input interface and the human performance, some instances might be very difficult to get (for example, if someone is typing on a QWERTY keyboard, it is easy for him to type ‘y’ to ‘u’, but he might type thousands of phrases to make a substitution error of typing ‘a’ into ‘b’).

Even we can get all instances, it does not mean that the distribution of each instance matches the ideal transmission distribution, which requires even more data to approach. Thus our practical solution is to use the overall probability to represent each instance’s probability. For example, use the overall substitution probability to represent each substitution instances:

P(‘b’|‘a’) = P(‘c’|‘a’) = … = P(substitution)

Use the overall omission/insertion/typing correctly probability in the same way.

P(‘a’|‘a’) = P(‘b’|‘b’) = … = P(typing correctly)

The downside of using practical solutions is that the throughput gained this way is no longer a theoretically justified measure. However, we have to make a trade-off between usability and theory. Let’s see how it performs in real settings!

Experiments & Results

It’s kinda tricky to manipulate different speed-accuracy conditions for typing experiment. Thus we designed a game-like experience for the participants. First of all, there are five speed-accuracy (SA) conditions: Extremely Accurate (EA), Accurate (A), Neutral (N), Fast (F) and Extremely Fast (EF). For each condition, the participant will type for five minutes, and every time he completes a phrase, he will get a score. At the end of each condition, the money will be rewarded according to the total score.

The tricky part lies in the score rules. From EA to EF, we decreased the score for completing each phrase. For example, successfully complete a phrase in EA results in 10 scores, while in EF results in 6 score. Thus to get equal score amounts, one has to type more phrases in fast conditions. There is also error criteria for each condition, and it looses from EA to EF: for EA conditions, one has to type each character correctly without making revisions to get the score, otherwise he will have no score or loose score; for EF conditions, one can make up to 15 errors to get the score.

This makes sure that people will adjust their SA strategy to gain higher scores in different SA conditions. Sounds fun, huh?

The TextTest++ interface. The timer is on the left; the condition selector and total score are on the right. After typing in the middle text area, participants could hit the ENTER key or “Next” button to go to the next phrase. (b) Indicators shown after finishing each phrase corresponding to the score increasing, no change, or decreasing, respectively.

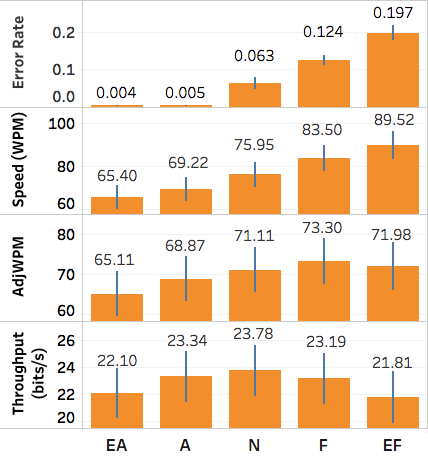

We conducted text studies on both QWERTY keyboard and smartphone keyboard. We compared four metrics: speed/error rate (uncorrected)/adjusted speed/throughput. Adjusted Speed (AdjWPM) = raw speed (WPM) * (1-error rate), it is to compensate the speed with the error term. The results of the QWERTY keyboard is shown below:

Results for the laptop keyboard in five cognitive sets, from Extremely Accurate to Extremely Fast. Error bars represent ±1 standard error. Note the very different y-axis ranges, which are set for visual comparison of differences within each metric across speed-accuracy conditions.

As we can see, the throughput indeed is the most stable metric across different conditions. For further analysis, we used the Coefficient of Variation to measure the variance among the different groups of data, and we used non-parametric analysis to test the difference between each condition. Finally, we used bootstrapping and confidence intervals to measure the similarity between each condition. All results indicate that the throughput is quite stable across different SA conditions, which is exactly what we want. (For analysis details, please read our paper).

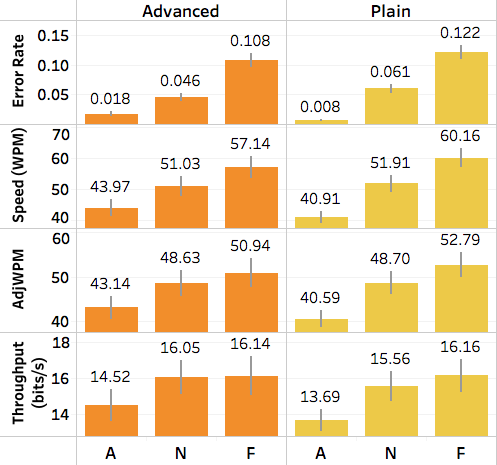

For mobile phone keyboard, we only manipulated three SA conditions (A/N/F), and the results are shown below. “Advanced” means the condition where the advanced functions (auto-correction, auto-completion, word-prediction) were used, and “plain” means no advanced functions were used. As we can see, the variance between A/N/F is slightly larger than the QWERTY keyboard. It might due to making corrections and typing every character correctly on a touch screen was more difficult than doing so on a physical keyboard, thus leading to a larger difference in throughput.

Closing Phrase

In my mind, throughput to text entry is like Fitts’ law to pointing. They both measure at the performance level, and also incorporate the speed-accuracy trade-off.

Our hope is that throughput will be calculated and reported to support comparisons across devices, text entry methods, and participants. The advantageous properties of throughput and the theoretical derivation from information theory make it suitable as a performance-level metric.

For your convenience, we open-sourced our text study interface TextTest++ here at GitHub, and also our algorithm for calculating the throughput here. Enjoy!